|

Let's not mince words: as Lawrence Kramer aptly declares, Maurice Ravel's Daphnis et Chloé culminates in "the most explicit representation of orgasm in all 'classical' music." Whether out of innocence or, more likely, discretion, other writers routinely underplay the matter, politely describing it as "rousing" (Lawrence Davies), "hectic" (Joseph Machlis), "a throbbing rhythm … joyful and tumultuous" (Arbie Orenstein), and "a gradual increase of activity that carries all before it" (Douglas Lee). The score itself denotes only a "joyous tumult." Maurice Ravel's Daphnis et Chloé culminates in "the most explicit representation of orgasm in all 'classical' music." Whether out of innocence or, more likely, discretion, other writers routinely underplay the matter, politely describing it as "rousing" (Lawrence Davies), "hectic" (Joseph Machlis), "a throbbing rhythm … joyful and tumultuous" (Arbie Orenstein), and "a gradual increase of activity that carries all before it" (Douglas Lee). The score itself denotes only a "joyous tumult."

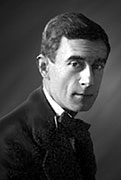

Remarkably, such a boldly impassioned work came from the pen of an outwardly conservative composer who was described by his early biographer Alexis Roland-Manuel as resembling a jockey - taut with bony features, barely five feet tall and weighing 108 lbs. Meticulously groomed, and a fastidious dresser, he never married. (Yet, as Gerald Larner points out, Baudelaire insisted that dandyism is not a deviant obsession with material elegance but rather "a symbol of the aristocratic superiority of the mind.")

Remarkably, such a boldly impassioned work came from the pen of an outwardly conservative composer who was described by his early biographer Alexis Roland-Manuel as resembling a jockey - taut with bony features, barely five feet tall and weighing 108 lbs. Meticulously groomed, and a fastidious dresser, he never married. (Yet, as Gerald Larner points out, Baudelaire insisted that dandyism is not a deviant obsession with material elegance but rather "a symbol of the aristocratic superiority of the mind.")

Yet Ravel's personality was tempered by a rebellious streak.

Ravel in 1907 and 1912

|

He was a founding member of the "Apaches," a circle of rising artists who took their ironic name from a gang of violent Parisian hooligans and banded together to champion modern music and art. His first attempt at the coveted Prix de Rome in 1901 insulted the jury, as he considered the prescribed text for the required cantata to be insipid and stuffy and so he facetiously set it as a waltz. That, in turn, led to "l'affaire Ravel," a scandal that rocked the Conservatory in 1905 when Ravel was disqualified from competing again, ostensibly for a lack of sufficient technical ability (despite having already published several masterworks that eclipsed those of all but one of his judges). Perhaps to show his defiance and in reaction to the conservative bureaucracy of the reigning Société Nationale de Musique, he later organized a Société Musicale Indépendente.

The Apaches helped to expand Ravel's musical horizons, and indeed he absorbed a variety of influences. Orenstein notes that his models were Mozart, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Satie and Fauré for their classical sense of structure, the Russian school for its spontaneity, orchestral color, exoticism and modality, the Basque and Spanish for their stirring treatment of rhythm, and the "New Viennese" school of Schoenberg, Berg and Webern for their meticulous craftsmanship. At the same time, he claimed to have reservations about Beethoven, Berlioz, Wagner and Tchaikovsky for their expressive architecture and metaphysical aspirations. Deborah Mawer adds that Ravel remained fascinated by dance (and conceived or adapted an unusually large portion of his major works for ballet), ranging from the ancient (minuet, pavane, forlane), through romantic (waltz), to modern Spanish (habanera, bolero), the last derived from his roots, as he was born and raised in a seacoast village on the French-Basque border. She adds that theater had a special appeal to Ravel in light of his personal reticence, as it enables the performers to "mask" themselves through assuming other roles.

Consistent with his fastidious personality, Ravel was a meticulous composer. He cited his objective as technical perfection, liked to be compared to an artisan and often quoted Baudelaire's aphorism: "Inspiration is the sister of daily work." According to Roland-Manuel, Ravel "viewed his role as that of a craftsman arranging tones, rather than a philosopher thinking with tones." Grove's Dictionary considered him "first and foremost a pure musician - always guided by properties of musical substance, a sensitive ear, an alert sense of proportion." Douglas Lee sums up Ravel's approach as lucidity, sophistication and polished craftsmanship.

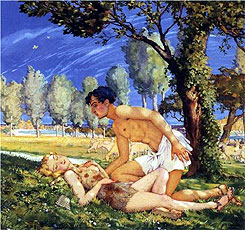

Daphnis & Chloe by Konstantin Somov (1930)

|

That impression often is underscored through contrast with Claude Debussy, the leading French composer of their generation, whose approach is considered instinctive and emotional when compared to Ravel's objective precision. Harold Schonberg sums up the difference as an etching (Ravel) versus a watercolor (Debussy).

Despite his reserve, the area in which Ravel's supremacy is universally praised is orchestration. Even so, he conceived only a handful of works for orchestra (Rapsodie espagnol, La valse, Bolero and Daphnis - and even those were sketched at the keyboard). All the rest were arrangements of his piano originals. Ironically, Ravel is perhaps best known for a work he didn't write - his orchestration of Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition which, Larner quips, "is so well known that the original is in danger of sounding like a piano arrangement" of Ravel's masterful adaptation. Daphnis is scored for a huge orchestra, including piccolo, flutes, alto flute, oboes, English horn, petite clarinet, clarinets, bass clarinet, bassoons, contrabassoon, horns, trumpets, trombones, tubas, harps, 13 percussion, a wind machine, divided strings and four-part chorus.

Generally acclaimed as Ravel's masterpiece, his completion of Daphnis was long and hard. Ravel considered a long period of gestation necessary: "During this interval I gradually come to see, with growing precision, the form and evolution which the subsequent work should have as a whole. I may thus be occupied for years without writing a single note of the work." Even after writing, he felt that "there is still more time to be spent in eliminating everything that might be regarded as superfluous, in order to realize as completely as possible the longed-for final clarity." Ravel considered himself a failure for having produced relatively few works in his life. Yet, Benjamin Ivry defends his output as emphasizing quality over quantity, as nearly all is of permanent value, and asks rhetorically how many works were needed to make Vermeer an immortal painter. Ravel wrote: "I did my work slowly, drop by drop. I have torn all of it out of me by pieces." In a 1928 memoir, he recalled that he had begun sketching the score for Daphnis in 1907, but scholars tend to correct this to 1909. By 1911, he had reached an impasse with the final bacchanal, turned to less demanding projects and asked his friend Louis Aubert to complete the work in exchange for full credit. Aubert later said, "The greatest service I ever gave music was convincing the great Ravel that he should finish his greatest work. In that respect I am a great composer." In a burst of final inspiration, Ravel completed Daphnis in two weeks.

Daphnis is not absolute music (even though it most often is heard that way) but rather the score to a ballet, a collaborative project whose creators had fundamentally disparate aims and told differing versions of the process of its creation, to which they all made essential contributions.

Daphnis is not absolute music (even though it most often is heard that way) but rather the score to a ballet, a collaborative project whose creators had fundamentally disparate aims and told differing versions of the process of its creation, to which they all made essential contributions.

RAVEL - Ravel asserted: "My intention in writing [Daphnis] was to compose a vast musical fresco, less concerned with archaism than with faithfulness to the Greece of my dreams, which is similar to that imagined and depicted by French artists at the end of the eighteenth century." As explained by Lawrence Davies, Ravel had never visited Greece and had no direct knowledge of authentic ancient culture; rather, typical of the Hellenism of educated Frenchmen of his time, he envisioned an idealized antiquity imbued with purity and clarity of mind, and willingly distorted the values of his own age with the perspective of that romanticized past.  The result, in Mawer's view, was a "pastoral idyll of classical purity and innocence" that meshed well with Ravel's artistic persona. Indeed, the overall chastity of the Daphnis story, its absence of sexual passion (until the final outburst), and its power to motivate this apex of Ravel's art, all led Ivry to assert that Ravel was a secretive gay man and to devote much of his 2000 biography to tracing Ravel's upbringing and life with an emphasis on exploring the relationship of homosexual influences, sayings, allusions, friends and possible lovers to the sexual undertones Ivry finds in much of Ravel's work. He notes in particular that Pan, the dominant deity in Daphnis, was a symbol to the Greeks of male homosexual activity. Most of Ravel's other biographers, though, reject that view (or, perhaps out of discretion choose to ignore it) and note that although Ravel never married he had many female friends and frequented female prostitutes. (Robert Craft quite recently has asserted that Stravinsky and Ravel were lovers.) The result, in Mawer's view, was a "pastoral idyll of classical purity and innocence" that meshed well with Ravel's artistic persona. Indeed, the overall chastity of the Daphnis story, its absence of sexual passion (until the final outburst), and its power to motivate this apex of Ravel's art, all led Ivry to assert that Ravel was a secretive gay man and to devote much of his 2000 biography to tracing Ravel's upbringing and life with an emphasis on exploring the relationship of homosexual influences, sayings, allusions, friends and possible lovers to the sexual undertones Ivry finds in much of Ravel's work. He notes in particular that Pan, the dominant deity in Daphnis, was a symbol to the Greeks of male homosexual activity. Most of Ravel's other biographers, though, reject that view (or, perhaps out of discretion choose to ignore it) and note that although Ravel never married he had many female friends and frequented female prostitutes. (Robert Craft quite recently has asserted that Stravinsky and Ravel were lovers.)

As for the musical structure of Daphnis Ravel wrote: "My work is constructed symphonically according to a very strict tonal scheme by means of a few motifs: their development assures the work symphonic homogeneity." Yet while it is true that Ravel assigned distinctive motifs and instruments to personify each main character, their mere repetition in various contexts falls short of the essence of a symphony, in which motifs are organically developed to generate a sense of inevitable forward progress. Rather, as Orenstein points out, Ravel was essentially a miniaturist and unified his larger works through repetition of a small number of motifs. Ravel's innovation in Daphnis was to create a through-composed score rather than a series of separate dances that informed traditional ballet. Lawrence Kramer credits the score with a brimful of exotic scales, colors, melody and instrumentation, derived in part from the sound-world of orientalist operas (Samson et Delilah, Prince Igor, Salome) and the symphonic Arabian music of Rimsky-Korsakoff's Scheherazade, presenting Ravel's European audience with a living museum of glimpses into their cultural origins as well as a tantalizing, dream-like taste of remote pleasures, but all in a "safe" remove, as if the ancient exoticism had been colonized in a triumph of European imperialism. presenting Ravel's European audience with a living museum of glimpses into their cultural origins as well as a tantalizing, dream-like taste of remote pleasures, but all in a "safe" remove, as if the ancient exoticism had been colonized in a triumph of European imperialism.

Ravel obtains a wide range of textures and spatial effects by constantly dividing his strings into eight parts, frequently using mutes and string playing on fingerboards, and placing instruments behind the stage. The chorus, too, is directed to sing variously behind, near or on stage and with open or closed mouths. Kramer further cites as an innovation the prominence of the entirely wordless vocals, far removed from European choral tradition but evoking both the ancient roots of singing and the sensory essence of modern life. Yet, true to form, even in the most heavily-scored passages, the sonority remains transparent. Lawrence Davies credits "Ravel's bright colors and sharply picked-out instrumentation" as enormously influential, enabling French music to "emerge from beneath the protective shell of Wagnerism" and its thick, rich sonorities. Ravel also was intrigued by the industrial sound of factories, and their regular pounding rhythms clearly found their way into the closing moments of Daphnis. Edward Downes adds that "with all its brilliant orchestration, intoxicating color [and] sensuous harmonies" Daphnis remains "an essentially patrician score" and that Ravel, "a spiritual aristocrat," never once "relax[ed] his mastery of form and precise craftsmanship."

In addition to its wide-ranging tonal centers, with key signatures ranging from six flats to seven sharps, Daphnis is notable for its unconventional rhythms. Most of the dance contest in Part I is in 7/4 time, with the first two measures shown for guidance as (3+4) /4. The bacchanal is in 5/4, with each measure divided by a dashed bar line into 2/4 and 3/4 (reportedly the dancers tried to keep count by chanting the name of the impresario "Ser-gei-Dia-ghi-lev"), before accelerating into pure 3/4 and finally 2/4 for the thrilling finish. But even much of the remainder departs from steady beats, with unprepared accents, constant sudden tempo adjustments (even directing cédez and pressez in the same bar), improvisatory solo flights with which the accompaniment is instructed to keep pace, and odd measures tossed in amidst regular beats, all of which disrupt any sense of a steady pulse and essentially require that the dancers simply have the complex score in their heads in order to feel the music and properly coordinate their moves. Although the dancers were distraught by Daphnis, its challenges would pale the following year when they had to confront the rhythmic terrors of Stravinsky's Rite of Spring.

FOKINE - The libretto was crafted by Mikhail Fokine, who had urged reform by presenting his strong artistic ideas in a 1904 manifesto to the directors of the Maryinksy theatre.  As summarized by Bill Zakariasen, Fokine wanted to move dance away from stylized formalization to create a connected dramatic experience in the service of great music, an approach clearly consistent with Ravel's own. Fokine envisioned dance as continuous and interpretive, with free artistic expression to convey the entire meaning of the story, while avoiding separation into numbers, reliance upon clichéd steps and stylized gestures, degeneration into gymnastic displays and interruptions to acknowledge applause. Fokine has left us the most detailed recollection of his collaborative process with Ravel, although it's clearly one-sided and was written decades later. He wrote that he liked Ravel's musical ideas, as he envisioned a score with emotion that would inspire the dancers' movements and with motifs based on character and situations, but without Wagnerian weight, and was delighted that the music would be unusual, colorful and unlike any other. Yet something happened along the way to spoil their relationship. According to Fokine, they had only one difference of opinion - he wanted an extended and violent dramatic sequence for the pirate attack, whereas Ravel wanted a lightning strike; Ravel prevailed, but Fokine later regretted his timidity. With that sole exception, Fokine claimed to have loved the score from the first time he heard it. Ravel, though, had a far different version of their relationship. In a June 1909 letter, Ravel wrote: "What complicates things is that Fokine doesn't know a word of French and I only know how to swear in Russian. In spite of the interpreter, you can imagine the savor of these meetings." Prior to his next ballet project, Ravel wrote the theatre administrator: "I would prefer to write [the libretto] myself, with some guidance. The precedent of Daphnis et Chloé, whose libretto was a source of perpetual conflict, has made me extremely reluctant to undertake a similar experience again." As summarized by Bill Zakariasen, Fokine wanted to move dance away from stylized formalization to create a connected dramatic experience in the service of great music, an approach clearly consistent with Ravel's own. Fokine envisioned dance as continuous and interpretive, with free artistic expression to convey the entire meaning of the story, while avoiding separation into numbers, reliance upon clichéd steps and stylized gestures, degeneration into gymnastic displays and interruptions to acknowledge applause. Fokine has left us the most detailed recollection of his collaborative process with Ravel, although it's clearly one-sided and was written decades later. He wrote that he liked Ravel's musical ideas, as he envisioned a score with emotion that would inspire the dancers' movements and with motifs based on character and situations, but without Wagnerian weight, and was delighted that the music would be unusual, colorful and unlike any other. Yet something happened along the way to spoil their relationship. According to Fokine, they had only one difference of opinion - he wanted an extended and violent dramatic sequence for the pirate attack, whereas Ravel wanted a lightning strike; Ravel prevailed, but Fokine later regretted his timidity. With that sole exception, Fokine claimed to have loved the score from the first time he heard it. Ravel, though, had a far different version of their relationship. In a June 1909 letter, Ravel wrote: "What complicates things is that Fokine doesn't know a word of French and I only know how to swear in Russian. In spite of the interpreter, you can imagine the savor of these meetings." Prior to his next ballet project, Ravel wrote the theatre administrator: "I would prefer to write [the libretto] myself, with some guidance. The precedent of Daphnis et Chloé, whose libretto was a source of perpetual conflict, has made me extremely reluctant to undertake a similar experience again."

Fokine also choreographed Daphnis.

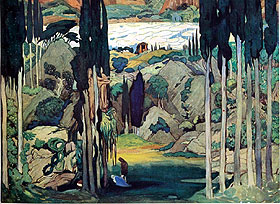

The grotto set by Bakst

|

Mawer identifies four primary types of dance in the ballet: ritual (deep-rooted pagan spirituality, suggesting an extended lineage from some presumed legendary primordium), high-speed (celebrating the sheer excitement of rapid movement), character-portraying (an individual aria without words) and exotic (with deeply-felt rhythm). Conspicuously missing were the gracious ensemble pieces and amorous pas de deux that audiences had come to expect, if not demand, from traditional ballet.

BAKST - The sets and costuming were by Léon Bakst, who visualized the scenic design as one of authenticity based upon an ancient Greece reconstructed by researchers, rather than as romanticized by French painters. His approach was consistent with Fokine, who envisioned a tale "of literal archaism in terms of Greek pagan dance with an erotic physicality" based on depictions on Greek vases. Clearly, their concept of archaic stylization was far removed from Ravel's. Pressed for time, Bakst adapted the scenery and outfits he had crafted for the Greek-themed Narcissus ballet he had mounted in the prior Russian Ballet season. The surviving pictures of the formalized sets and costumes seem vastly discordant with Ravel's lush and sensual music.

DIAGHILEV - Perhaps the strongest influence came from Sergei Diaghilev, a Russian impresario who began exhibiting Russian art in Paris in 1906, and then expanded into opera, concerts and ballet.  Upon losing the support of a key patron in 1908, he created his own troupe, the Ballets Russes, and for the 1909 season turned to Western composers for fresh ideas and commissioned new works that would break away from stale formulas and that could hold their own with audiences enthralled by star dancers. At first he was greatly impressed with Ravel's ideas for modernizing the music of ballet, but, as with Fokine, their relationship soured and then turned turbulent. Amid violent disagreements with Fokine and Bakst, Diaghilev wanted to cancel Daphnis but Fokine refused. Instead, perhaps to assert his authority, Diaghilev hobbled the premiere, scheduling it at the end of the season and placing it first on a long program scheduled to begin earlier than usual and before the fashionable segment of the audience would arrive. In an obvious dig at Diaghilev, Ravel wrote a February 1912 letter to another producer stating, "Above all … I wish to express to you my pleasure at having just met an artistic director whose consistent concern is to respect the composer's ideas while assisting him with the kind of intelligent advice that comes from a gentleman of taste." Even so, and while they never worked together again, Ravel dedicated the Daphnis score to Diaghilev. Upon losing the support of a key patron in 1908, he created his own troupe, the Ballets Russes, and for the 1909 season turned to Western composers for fresh ideas and commissioned new works that would break away from stale formulas and that could hold their own with audiences enthralled by star dancers. At first he was greatly impressed with Ravel's ideas for modernizing the music of ballet, but, as with Fokine, their relationship soured and then turned turbulent. Amid violent disagreements with Fokine and Bakst, Diaghilev wanted to cancel Daphnis but Fokine refused. Instead, perhaps to assert his authority, Diaghilev hobbled the premiere, scheduling it at the end of the season and placing it first on a long program scheduled to begin earlier than usual and before the fashionable segment of the audience would arrive. In an obvious dig at Diaghilev, Ravel wrote a February 1912 letter to another producer stating, "Above all … I wish to express to you my pleasure at having just met an artistic director whose consistent concern is to respect the composer's ideas while assisting him with the kind of intelligent advice that comes from a gentleman of taste." Even so, and while they never worked together again, Ravel dedicated the Daphnis score to Diaghilev.

The premiere was further compromised by inevitable comparisons with the sensational unveiling the week before of another Diaghilev production - a ballet set to Debussy's Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun and the scandal of its overtly sexual choreography, ending in (presumably feigned) masturbation with flowing veils. (A Daphnis revival the following year would be eclipsed again, this time by the Rite of Spring.) Although barely one-sixth as long, the Faun required 120 rehearsals, leaving too few for the far greater complexity of Daphnis. Thus one critic complained that the music had been betrayed by a negligent production and performance, and another, clearly a traditionalist, objected that it had "very little grace, very little charm and above all very little inspiration." (A third, presumably overlooking the innovative time signatures - and perhaps having left before the end - caviled that it lacked "the first quality of ballet music: rhythm.")

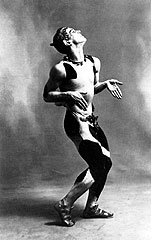

Nijinsky as the Faun

|

It seems highly ironic that Debussy's Faun turned out to be the work that spoiled the Daphnis premiere, as it earlier had served as prime inspiration for Ravel's career - Ravel wrote that upon hearing Debussy's 1894 score he was "profoundly moved," that it "appeared to open up innumerable unexplored horizons" and that it led him to understand what music was all about. Later, though, he would come to resent the attention lavished upon Debussy and especially his piano music which, Ravel pointed out, was heavily influenced by Ravel's 1902 Jeux d'Eau, leading to the two composers' estrangement. (Undoubtedly, Ravel's support of Debussy's abandoned wife didn't help.)

NIJINSKY - One reason for Diaghilev's attitude, and for the attention he lavished on the Faun, was his (literal) love for its legendary lead dancer, Vaslav Nijinsky, who also danced the lead male role in Daphnis, and whose spectacular floating leaps may have inspired some of the soaring figures in Ravel's score. (When asked for the secret of this astounding technique, Nijinsky reportedly said it was easy - he just paused before coming back down.) Victor Seroff faulted Diaghilev for assuming that Nijinsky's brilliance as a dancer endowed him with genius as a choreographer, despite his lack of "education, culture, taste and above all vision and the ability to communicate his ideas to others." In any event, Diaghilev's unwavering support for Nijinsky's explicit eroticism caused his rift with Fokine and, of course, the circumspect Ravel.

The basic story is a drastic condensation of the only surviving work of Longus, presumed to have been a second-century Greek novelist but of whom nothing is known. His Daphnis and Chloé is a concise but sweeping tale of a shepherd and shepherdess discovering and exploring their love despite obstacles, separation and adventure.

The basic story is a drastic condensation of the only surviving work of Longus, presumed to have been a second-century Greek novelist but of whom nothing is known. His Daphnis and Chloé is a concise but sweeping tale of a shepherd and shepherdess discovering and exploring their love despite obstacles, separation and adventure.

Woodcut by Maillol

|

Universal in its humanity, disarming in its careful observation of nature and thoroughly modern in its psychology, its genesis a hundred generations ago is remarkable. Indeed it eloquently attests to the consistency of human aspirations since ancient times. Its ending typifies its modest, subtle power - as Daphnis and Chloé are finally married and about to make love for the first time, Longus affords us a brief comforting glimpse into their future of deepening fulfillment and then takes leave with affecting simplicity and sly humor: "and for all the sleep they got that night they might as well have been owls."

Not only did Fokine whittle the Longus plot down to a rudimentary sketch, but he shrunk the characters into simplistic stereotypes: in the novel, the older shepherdess Lyceion doesn't merely flirt with Daphnis but patiently teaches him the art of love, and his rival Dorcon isn't a mere laughable buffoon but a complex, spurned suitor who remains so devoted to Chloé that he dies trying to save her from abduction. But worst of all, as many commentators have noted, Fokine emasculated the original story, as the forthright eroticism that animates the novel became a chaste formalized ritual - indeed, although supposedly burning with desire, Daphnis and Chloé barely touch each other.

The ballet is in a single continuous act, divided into three tableaux comprising twelve scenes:

- Tableau I - A Grotto

Daphnis & Chloe by Marc Chagal (1961)

|

- Scene 1 - Introduction et danse religieuse - In a grotto, a crowd of youngsters bow before an alter of nymphs. Girls dance around the shepherd Daphnis, kindling Chloé's jealousy.

- Scene 2 - Danse générale - The cowherd Dorcon competes for Chloé's attention. A dance contest is proposed for a kiss from Chloé.

- Scene 3 - Danse grotesque de Dorcon - The crowd mocks the rival suitor's clumsy motions.

- Scene 4 - Danse légère et gracieuse de Daphnis - With a light and graceful dance Daphnis wins the contest and accepts his reward. Daphnis and Chloé embrace. The crowd withdraws with Chloé, leaving Daphnis in ecstasy.

- Scene 5 - Danse de Lycéion - Another shepherdess, Lyceion, tries to entice Daphnis. Pirates attack. Chloé beseeches the nymphs' protection but is carried off.

- Scene 6 - Nocturne. Danse lente et mystérieuse des Nymphes - Daphnis searches for Chloé but collapses in despair. The nymphs come to life, revive Daphnis and supplicate Pan, the god of the shepherds.

- Tableau II - The Pirates' Camp

- Scene 7 - Introduction - The pirates bring in their plunder.

- Scene 8 - Danse guerrière - They exhaust themselves in a war-like dance. Their chief orders Chloé to dance.

- Scene 9 - Danse suppliante de Chloé - As she dances in supplication, Chloé tries to escape. As the chief carries her off fantastic satyrs surround the pirates. Pan appears and the terrified pirates flee.

- Tableau III - The Grotto at Night

- Scene 10 - Lever du jour - As day breaks, Daphnis and Chloé are reunited. An old shepherd Lammon explains that Pan intervened in memory of his own love of the nymph Syrinx.

- Scene 11 - Pantomime (Les amours de Pan et Syrinx) - The couple mime the tale of Pan's courtship of Syrinx, whom he enchanted with a flute of reeds. Before the nymphs' altar Daphnis pledges his love for Chloé.

- Scene 12 - Danse générale (Bacchanale) - As they tenderly embrace, the entire company joins in a wild joyous dance.

Although continuous, the score is full of highlights.

THE THIRD TABLEAU

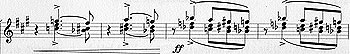

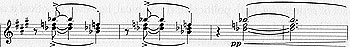

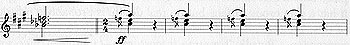

Day breaks

The beauty of nature

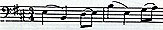

The final gasps of orgasm (soprano and alto parts)

(from Kramer's Classical Music and Post-Modern Knowledge)

|

The magical opening evokes primeval wonder as instruments and voices grope for melody amid searching harmonies, their ebb and flow dissolving into a meltingly lovely theme that awakens in wonder and innocence as the materials become more refined and begin to coalesce. The dances that follow begin in gentle, teasing flirtation, then mock Dorcon more pathetically than cruelly, present Daphnis lightly and in uncertain rhythm so as to portray his innocence, uncertainty and inexperience in courtship, and end fitfully with his bewilderment at Lycéion's advances. The former motifs are torn in explosive dissonance as the pirates attack, and then subside into a suffusion of mystery as the nymphs stir to life (with help from the wind machine) and comfort Daphnis. The wordless chorus reverts to timeless mystery to introduce the second tableau, and swiftly builds to an outburst of the pirates' gruff vigor, their incessant stomping rhythm disrupting the bittersweet melancholy of Chloé's dance of supplication. The music then subsides into tense expectation before Pan decisively restores order.

For those seeking a more concentrated experience in keeping with the demands of our hurried times, the third tableau (often performed alone as the second suite) provides an abundant and satisfying taste of the splendor of Ravel's achievement. As day breaks, nature slowly stirs to life - rivulets flow in harp arpeggios, birds chirp in the flutes, shepherds begin to stir, a gorgeous string theme evokes the sheer beauty of pristine nature, and the sun rises to its full brilliance as a simple repeated sequence builds into an astoundingly powerful climax. Indeed, the music of the opening scene is so masterfully suggestive by itself that a visual depiction on stage seems doomed to compromise its impact. John Culshaw views it as "Ravel as a man searching for a means to express the essence of beauty and finding it." Indeed, it just might be the most gorgeous few minutes of orchestral music ever written. Next, the gentle interplay of the pantomime provides a needed respite and at the same time is full of evocative melodic shreds to enable us to picture the narrative it was meant to accompany. The electrifying final pages simply defy description, other than to return to our initial thought, as the bacchanal surges and throws off constant sparks of euphoric energy as it inexorably builds to a final explosion of unbridled ecstasy.

Since we have few hints as to Ravel's own preferred orchestral style, we are fortunate that a remarkable number of the first three decades of Daphnis recordings were led by conductors who had significant ties to the composer. Victor Seroff considered him a "very poor conductor" who didn't succeed in bringing out the proper perspective of a piece, either overall or in the details, which he attributes to Ravel's lack of experience as a performer and a resultant lack of authority.

Ravel conducting

|

Indeed, he quotes Ravel as having said after a concert he had led: "I had no idea what was going on." Even during festivals of his music, Ravel generally declined the baton. Our only recording of Ravel as conductor is barely relevant - a rock-steady 1930 Bolero, but even then he was assisted by a more experienced conductor, Albert Wolff, his tempo is far slower than his own indication in the score, and in any event that piece is so atypical that little can be inferred - Ravel described it as "orchestral effects without music" and indeed it's nothing more than a single melody wending its way through the instruments. (A 1932 recording of Ravel's Piano Concerto in G with Marguerite Long, routinely attributed to Ravel, actually was conducted by Pedro de Freitas-Branco, who told the story of Ravel attempting to lead a "filler" side of his Pavane at a tempo that would have lasted nearly seven minutes, whereupon the producer took him out for a drink, Freitas-Branco cut the side speeded up to 4:32, and Ravel approved it.)  Although Ravel insisted that conductors adhere to the score (and even disparaged Toscanini, who held the score sacrosanct, as "one of those incorrigible virtuosi who go about daydreaming as if the composer didn't exist") he complimented others' interpretations and, indeed, even the players in his Bolero take substantial expressive liberties (including a wayward trombonist), albeit without altering the tempo. Several recordings that he supervised or approved display considerable tempo variations and, indeed, his piano professors at the Conservatory had criticized his playing as having "a great deal of temperament," "a tendency to pursue big effects," being "overly-enamored of violence" and "lapsing into exaggeration" (although from their rigid academic perspective the degree of Ravel's feeling may have been rather mild). Perhaps more revealing than his Bolero is the highly inflected 1927 recording he supervised by the International String Quartet of his Quartet in F, the score of which, like Daphnis, is full of expression markings (many of which the performers ignore). Although Ravel insisted that conductors adhere to the score (and even disparaged Toscanini, who held the score sacrosanct, as "one of those incorrigible virtuosi who go about daydreaming as if the composer didn't exist") he complimented others' interpretations and, indeed, even the players in his Bolero take substantial expressive liberties (including a wayward trombonist), albeit without altering the tempo. Several recordings that he supervised or approved display considerable tempo variations and, indeed, his piano professors at the Conservatory had criticized his playing as having "a great deal of temperament," "a tendency to pursue big effects," being "overly-enamored of violence" and "lapsing into exaggeration" (although from their rigid academic perspective the degree of Ravel's feeling may have been rather mild). Perhaps more revealing than his Bolero is the highly inflected 1927 recording he supervised by the International String Quartet of his Quartet in F, the score of which, like Daphnis, is full of expression markings (many of which the performers ignore).

Perhaps as a tribute to its essential continuity, no recording of the complete Daphnis score arose until well into the LP era (although there were plenty of Bruckner symphonies chopped into 78 rpm side lengths). Before then, the only Daphnis recordings were of the two suites that Ravel had extracted from the full score - a Suite # 1, comprising the Nocturne from Tableau I and the Interlude and Danse guerriere from Tableau II; and a Suite # 2, essentially the entirety of Tableau III (excepting only a ten-bar introduction).

Perhaps as a tribute to its essential continuity, no recording of the complete Daphnis score arose until well into the LP era (although there were plenty of Bruckner symphonies chopped into 78 rpm side lengths). Before then, the only Daphnis recordings were of the two suites that Ravel had extracted from the full score - a Suite # 1, comprising the Nocturne from Tableau I and the Interlude and Danse guerriere from Tableau II; and a Suite # 2, essentially the entirety of Tableau III (excepting only a ten-bar introduction).

The first Daphnis recording was of the Suite # 2, cut in late 1928 by Serge Koussevitzky leading the Boston Symphony Orchestra (Victor 78s, Pearl and BSO CDs; 15:33). Robert Cowan aptly describes it as "strong on sonority but weak on impulse," and, indeed, while it presents a smooth, blended evolution of orchestral color (with considerable portamento), it lacks the intensity of a 1944-5 Koussevitzky/Boston remake (Victor 78s; BMG CD; 14:58), which boasts cleaner articulation, a more powerful daybreak climax and a vastly more incisive general dance, abetted by more detailed, if thinner, sonics. Perhaps the reason for Koussevitzky's earlier reticence lay in a 1924 interview in which the composer had criticized the conductor as "a great virtuoso who always has a very personal style of interpretation, sometimes admirable, but sometimes mistaken." Later, Koussevitzky defended his approach: "A talented artist, no matter how accurately he follows the markings of the score, renders the composition through his own prism, his own perception, his own temperament and emotion. And the greater the emotion of the interpreter, the greater and more vivid the performance." cut in late 1928 by Serge Koussevitzky leading the Boston Symphony Orchestra (Victor 78s, Pearl and BSO CDs; 15:33). Robert Cowan aptly describes it as "strong on sonority but weak on impulse," and, indeed, while it presents a smooth, blended evolution of orchestral color (with considerable portamento), it lacks the intensity of a 1944-5 Koussevitzky/Boston remake (Victor 78s; BMG CD; 14:58), which boasts cleaner articulation, a more powerful daybreak climax and a vastly more incisive general dance, abetted by more detailed, if thinner, sonics. Perhaps the reason for Koussevitzky's earlier reticence lay in a 1924 interview in which the composer had criticized the conductor as "a great virtuoso who always has a very personal style of interpretation, sometimes admirable, but sometimes mistaken." Later, Koussevitzky defended his approach: "A talented artist, no matter how accurately he follows the markings of the score, renders the composition through his own prism, his own perception, his own temperament and emotion. And the greater the emotion of the interpreter, the greater and more vivid the performance."

The next Daphnis recording, also of the second suite, was from Philippe Gaubert conducting the Concerts Straram orchestra (March 1930, French Columbia 78s, VAI CD; 15:45). Koussevitzky had commissioned Ravel to prepare the now-famous orchestration of Moussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition in 1922, and had honored the composer with a festival and shared the baton of his orchestra during Ravel's only American tour in 1928, but Gaubert's bond with Ravel went even deeper - he had conducted Daphnis for its 1921 revival at the Paris Opera and, an acclaimed flutist, played under Ravel's personal supervision in the 1924 recording of Ravel's ravishing Introduction and Allegro. Reportedly, this Daphnis was the only one Ravel had in his personal record collection. Chief conductor of the Paris Opera and Conservatoire orchestras, Gaubert affords an opportunity to hear a quintessentially French reading. While his 1936 recording of the Tchaikovsky Pathetique is full of rich emotion, deep expression and sharp inflection and attests to his versatility, his Daphnis (as well as a 1927 La Valse that minimizes the acidic undertone) opts for smoothly flowing phrasing, finely judged balances and an overriding tenderness that present an evolutionary sense of continuity and unity, all within an aura of nonchalant diffidence that, more than any other trait, has come to define the French sensibility. Interestingly, the first Koussevitzky and Gaubert recordings are remarkably similar in feeling, from the barely audible twittering birds, which form more of a grace-note to the wonder of dawn than accurately following the score's specification of en dehors (prominently), to the deliberately attenuated climaxes, which emphasize classical grace over heart-pounding drama. but Gaubert's bond with Ravel went even deeper - he had conducted Daphnis for its 1921 revival at the Paris Opera and, an acclaimed flutist, played under Ravel's personal supervision in the 1924 recording of Ravel's ravishing Introduction and Allegro. Reportedly, this Daphnis was the only one Ravel had in his personal record collection. Chief conductor of the Paris Opera and Conservatoire orchestras, Gaubert affords an opportunity to hear a quintessentially French reading. While his 1936 recording of the Tchaikovsky Pathetique is full of rich emotion, deep expression and sharp inflection and attests to his versatility, his Daphnis (as well as a 1927 La Valse that minimizes the acidic undertone) opts for smoothly flowing phrasing, finely judged balances and an overriding tenderness that present an evolutionary sense of continuity and unity, all within an aura of nonchalant diffidence that, more than any other trait, has come to define the French sensibility. Interestingly, the first Koussevitzky and Gaubert recordings are remarkably similar in feeling, from the barely audible twittering birds, which form more of a grace-note to the wonder of dawn than accurately following the score's specification of en dehors (prominently), to the deliberately attenuated climaxes, which emphasize classical grace over heart-pounding drama.

Nearly all of the subsequent 78-era studio recordings of the second suite came from American orchestras and labels. Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra (1939; Victor 78s; 15:20) boasts beautiful playing with abundant feeling (perhaps surprisingly so, from a severely under-rated conductor) and a superbly detailed recording - but with the first side break placed disastrously right in the middle of the daybreak climax; Artur Rodzinski and the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra (1941, Columbia 78s; Lys CD; 14:20) is briskly paced, but rather brusque and detached; Fritz Reiner and the CBS Symphony (1945; V-Disc; Lys CD; 16:48) is bland overall, but with an uncommonly measured and patient pantomime section; and Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony (1949; RCA LP, BMG CD; 16:10) is precise but rather dry and mechanical with potent climaxes (albeit with considerable overload distortion); a 1938 NBC concert had allied equal power with more pliant phrasing. More interesting interpretatively were several concert readings, although none was released at the time. Willem Mengelberg and the Concertgebouw Orchestra of Amsterdam (1938; Audio Legends CD; 16:05) is colorful and expressive, reveling in the kaleidoscopic marvels of Ravel's textures and orchestration); Wilhelm Furtwangler and the Berlin Philharmonic (1944, DG CD; 16:30) is dark and impassioned, with scorching climaxes fueled by fearsome tympani, although relieved with far more repose and gentleness than one might expect in light of the oppressive time and place - perhaps both a reaction to and respite from the horrors of war - and, ironically, bridging the vast cultural gap between the music of France and that of Germany that he was so desperately trying to preserve; and Guido Cantelli and the New York Philharmonic (1951, AS Disc CD; 14:45) displays precision inherited from his mentor Toscanini, but youthfully fleet without seeming driven or rushed; a 1954 Rome RAI concert (Fonit Cetra LP, 13:35) is even faster, enlivened with a sense of constant forward momentum).

The far less popular Suite # 1 had been introduced and published in 1911, the year before the premiere, as a preview of the full ballet. Fittingly, its first recording came from Piero Coppola (1934, Gramophone 78, Lys CD).  Although Italian, Coppola directed the French branch of HMV and was tasked to achieve a nearly complete set of the Debussy and Ravel orchestral music. Cut toward the very end of that project, his Suite # 1 comprises only the Nocturne and Danse guerrière. Heard together nowadays the juxtaposition seems jarring, but in practice his omission of the interlude (undoubtedly to fit the rest onto a single 78) hardly mattered, since the disc had to be flipped over, creating a natural separation between the two parts. Leading the premiere orchestra in France at the time, the Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire, Coppola's reading is moderate and eminently sensible, atmospheric without any abrupt emphases or shifts, a style that came to be respected as authentic, not least by Ravel himself, who had anointed Coppola to cut the first recording of his infamous Bolero just days before the composer would direct his own rival edition. (Unlike many conductors who disdained recordings, as a loyal employee of HMV Coppola was quite conscious of how to sound good on records and produced many fine results; his 1927 Pavane pour un infante dèfunte, sped up to 4½ minutes to fit on a single 12" side, has a refreshing wistful quality rather than the funereal weight it often bears.) Strangely, despite the scope of HMV's goal, Coppola never recorded the Suite # 2. Although Italian, Coppola directed the French branch of HMV and was tasked to achieve a nearly complete set of the Debussy and Ravel orchestral music. Cut toward the very end of that project, his Suite # 1 comprises only the Nocturne and Danse guerrière. Heard together nowadays the juxtaposition seems jarring, but in practice his omission of the interlude (undoubtedly to fit the rest onto a single 78) hardly mattered, since the disc had to be flipped over, creating a natural separation between the two parts. Leading the premiere orchestra in France at the time, the Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire, Coppola's reading is moderate and eminently sensible, atmospheric without any abrupt emphases or shifts, a style that came to be respected as authentic, not least by Ravel himself, who had anointed Coppola to cut the first recording of his infamous Bolero just days before the composer would direct his own rival edition. (Unlike many conductors who disdained recordings, as a loyal employee of HMV Coppola was quite conscious of how to sound good on records and produced many fine results; his 1927 Pavane pour un infante dèfunte, sped up to 4½ minutes to fit on a single 12" side, has a refreshing wistful quality rather than the funereal weight it often bears.) Strangely, despite the scope of HMV's goal, Coppola never recorded the Suite # 2.

Two further recordings of the Suite # 1 arose in 1946. Charles Munch followed in Coppola's footsteps by leading the same Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire in the Nocturne and Danse guerrière (plus a fine Suite # 2 - Decca 78s; Lys CD) and Pierre Monteux led the San Francisco Symphony in the entire first suite, including the Interlude which, in context, provides a fitting transition between the languid Nocturne and urgent Danse (Victor 78s; BMG CD). Their significance transcends matters of interpretation, as they served as heralds of these important conductors' recordings of the full ballet.

The Monteux recording has further significance as the first to include the wordless chorus that seems such a crucial component of the score (and, while rare in the suites, is always included in recordings of the complete ballet).   Therein lies a tale. The full score, as published, contains an appendix providing an orchestrated version of the a capella Part II vocal introduction with a directive that it be used "for performances without choruses." Yet when Diaghilev mounted the ballet in London in 1914 and dispensed with the chorus as a needless expense Ravel was furious and wrote an open letter to the London papers, calling the all-orchestral alternative "a make-shift arrangement … in order to facilitate production in certain minor centers" and chided Diaghilev for considering London to be one: "I consider the proceedings to be as disrespectful to the London public as well as toward the composer." The upshot - Ravel bound Diaghilev to a contract requiring the use of a chorus in all further productions. Therein lies a tale. The full score, as published, contains an appendix providing an orchestrated version of the a capella Part II vocal introduction with a directive that it be used "for performances without choruses." Yet when Diaghilev mounted the ballet in London in 1914 and dispensed with the chorus as a needless expense Ravel was furious and wrote an open letter to the London papers, calling the all-orchestral alternative "a make-shift arrangement … in order to facilitate production in certain minor centers" and chided Diaghilev for considering London to be one: "I consider the proceedings to be as disrespectful to the London public as well as toward the composer." The upshot - Ravel bound Diaghilev to a contract requiring the use of a chorus in all further productions.

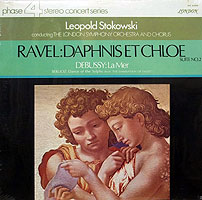

Among the dozens of later recordings of the Suite # 2, two seem of exceptional interest. Leopold Stokowski and the London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus (1970, London Phase 4 LP and London CD; 16:40) give a glorious, deeply engaged reading (although it may strike some as overly mannered) in which Stokowski and the engineers seemingly spotlight every player of every note, and it's one of the very few Suites with chorus - but why, oh why, did he have to spoil the end by tacking on a gratuitous a capella choral swell leading to an orchestral sting? For exquisite polish and sheer ravishing beauty, no other recording can compare to Sergiu Celibidache and the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra and Chorus ([date undetermined], Originals CD; 19:10). Their luxuriant unfolding of the score and the rivetingly powerful climaxes derive their full force from the sensational intrinsic balances among the musical materials. Sadly, it's hard to find and, to make matters worse, of the eight other concert recordings of the Suite # 2 listed in Celibidache discographies, I can vouch that the 1970 RAI Milan (Finit Cetra CD) and 1974 ORTF (Exclusive CD) are poorly-played and -recorded and don't even come close. EMI's omission of this (and superb concerts of the Sibelius Second and other significant works) from their 36-volume posthumous Celibidache Edition is criminal.

- Ernest Ansermet, Orchestre de la Suisse Romande (Decca, 1952; 53:30)

1952 finally brought a crucial development - the first of what soon would become a bounty of recordings of the complete ballet. The source was propitious. Ernest Ansermet (1883 - 1969) had succeeded Monteux as conductor of the Ballets Russes in 1915. Throughout his long career, while not immune to criticism of uninspired routine in other genres, his recordings of full-length Tchaikovsky, Stravinsky and other ballets were (and remain) exemplary, serving as constant reminders that these works were not conceived as symphonies or even tone poems but rather intended for the dance. Indeed, an essential component of Ansermet's style was his rhythmic steadiness and moderated transitions, which are vital to a successful presentation of ballet in which the dancers depend upon metric regularity and the absence of impulsive surprises in order to coordinate their moves. Ravel, who rarely spared criticism of those who led his works, praised Ansermet's understanding of La Valse as "perfect" and cited in particular his "rhythmic suppleness."   Moderate, steady and beautifully proportioned, this is at once a literal reading as well as a thoroughly convincing treatise of advocacy for the unadorned score. The conductor and composer were both close friends and an ideal esthetic match - Ansermet's art has been called "the poetry of precision," while he considered Ravel's poetry to have crystallized from melodic and rhythmic figures. The Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, which Ansermet founded in 1918 and led for nearly a half-century, is at one with its guide. Indeed, Ansermet is one of those extremely rare conductors whose style barely changed over the course of a 50-year recording career - aside from some slightly greater incisiveness, his first eight sides (with the Ballet Russes Orchestra in 1916) already boast the extraordinary balance, rhythmic vitality and precision that would typify his style from the acoustic to stereo eras. A final marvel is the exquisite sharpness and sonic detail of the recording itself, which serves as an object lesson for those who sadly think of the monaural format as incapable of conveying the "realism" of stereo (or quad or surround, for that matter). Indeed, it still sounds wonderful, perhaps in part because Ansermet reportedly adjusted dynamics and balances to sound well in a living room. Ansermet and the Suisse Romande remade Daphnis in stereo in 1965, but while that version is the one generally reissued and heard nowadays, it was slightly slower and more diffuse (by then the conductor was 82) and its gain in spatial soundstage is offset by a duller sound that, although perhaps more "natural," loses the riveting cutting-edge brilliance of the earlier one. In any event, with Ansermet the floodgates opened - from that point on, with very few exceptions, nearly every significant Daphnis recording would be of the full ballet. Moderate, steady and beautifully proportioned, this is at once a literal reading as well as a thoroughly convincing treatise of advocacy for the unadorned score. The conductor and composer were both close friends and an ideal esthetic match - Ansermet's art has been called "the poetry of precision," while he considered Ravel's poetry to have crystallized from melodic and rhythmic figures. The Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, which Ansermet founded in 1918 and led for nearly a half-century, is at one with its guide. Indeed, Ansermet is one of those extremely rare conductors whose style barely changed over the course of a 50-year recording career - aside from some slightly greater incisiveness, his first eight sides (with the Ballet Russes Orchestra in 1916) already boast the extraordinary balance, rhythmic vitality and precision that would typify his style from the acoustic to stereo eras. A final marvel is the exquisite sharpness and sonic detail of the recording itself, which serves as an object lesson for those who sadly think of the monaural format as incapable of conveying the "realism" of stereo (or quad or surround, for that matter). Indeed, it still sounds wonderful, perhaps in part because Ansermet reportedly adjusted dynamics and balances to sound well in a living room. Ansermet and the Suisse Romande remade Daphnis in stereo in 1965, but while that version is the one generally reissued and heard nowadays, it was slightly slower and more diffuse (by then the conductor was 82) and its gain in spatial soundstage is offset by a duller sound that, although perhaps more "natural," loses the riveting cutting-edge brilliance of the earlier one. In any event, with Ansermet the floodgates opened - from that point on, with very few exceptions, nearly every significant Daphnis recording would be of the full ballet.

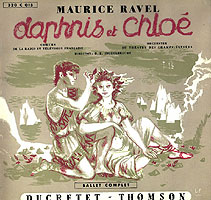

- Désiré Inghelbrecht, Choeurs et Orchestre National de la Radiodiffusion Française (1953, Ducretet-Thomson LP, Testament CD; 53:30)

Remarkably, the very next complete Daphnis provided the opposite side of the interpretive coin - overt drama fueled by vastly powerful emphatic surges, dynamics and tempo shifts. The contrast with Ansermet is apparent from the very outset - Ansermet's carefully groomed and layered evolutionary sonic swells become sharp highly-charged explosions of surging vitality - and later in the pirate invasion Ansermet's polite tingling bells become a clanging alarm. While such an approach would seem overwhelming as accompaniment to ballet, it seems fully appropriate to sustain interest as a purely auditory experience, shorn of the complementary narrative stage action, especially in the rather lengthy, musically uneventful and somewhat barren stretches of the first part. Yet the emotional surfeit could be deemed antithetical to Ravel's fundamental delicacy. Even so, Inghelbrecht's approach cannot be discounted as that of an outsider - as a member of the Apaches he had the longest relationship to Ravel of any conductor on record. Indeed, despite personal coolness that developed, Ravel called him "a remarkable musician," was "struck by [his] exceptional skill and understanding" and in 1910 personally recommended him for the prestigious position of conductor of the Parisian Théâtre des Arts. (Inghelbrecht was even closer to Debussy, of whose works he made numerous recordings that tended to be more leisurely than his Daphnis, although still quite trenchant, and are still vaunted for their "French" quality, as is fitting for a musician who rarely ventured outside his native land and played a leading role in its culture, founding its first permanent orchestra, the famed (and aptly named) Orchestre National de France.) In any event, whether or not aligned with the composer's underlying intentions, for better or for worse it cannot be denied that Inghelbrecht's approach has become increasingly dominant in our age of home listening, increased distractions and reduced attention spans in which a galvanic recording has to bear the entire burden of our experience.

- Antal Dorati, Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, Macalester College Choir of St. Paul (1954, Mercury LP; 51:15)

The following year brought yet another contrast, geographically and culturally distant from European tradition.  Although the timing would suggest a more urgent infusion of energy than Dorati's predecessors, his interpretation is rather neutral and leaves an impression more of dispassionate mechanics than persuasive engagement. Despite the breadth of his repertoire and the strength of his recorded legacy (including the first integral set of the Tchaikovsky ballets), Dorati seemed to have had little empathy for French music, and in retrospect it seems a shame that the first American opportunity to record the complete Daphnis had not been given instead to his label-mate Paul Paray, whose 1961 reading of the Suite # 2 with the Detroit Symphony surged with power and grace. The recording itself, though, is notable for its detail without the clinical precision of the Ansermet, and is infused with the natural ambiance of an actual auditorium, due in large part to the use of Mercury's famed single microphone technique that was intended to replicate the sound that would be experienced by a theatre audience. The album was enhanced with a gatefold format featuring a cover drawing by Aristide Maillol and a booklet with further illustrations and extensive text. Although the timing would suggest a more urgent infusion of energy than Dorati's predecessors, his interpretation is rather neutral and leaves an impression more of dispassionate mechanics than persuasive engagement. Despite the breadth of his repertoire and the strength of his recorded legacy (including the first integral set of the Tchaikovsky ballets), Dorati seemed to have had little empathy for French music, and in retrospect it seems a shame that the first American opportunity to record the complete Daphnis had not been given instead to his label-mate Paul Paray, whose 1961 reading of the Suite # 2 with the Detroit Symphony surged with power and grace. The recording itself, though, is notable for its detail without the clinical precision of the Ansermet, and is infused with the natural ambiance of an actual auditorium, due in large part to the use of Mercury's famed single microphone technique that was intended to replicate the sound that would be experienced by a theatre audience. The album was enhanced with a gatefold format featuring a cover drawing by Aristide Maillol and a booklet with further illustrations and extensive text.

- Charles Munch, Boston Symphony Orchestra, New England Conservatory Chorus and Alumni Chorus (1955, RCA LP, BMG CD; 54:25)

By reputation a French specialist, Munch actually was Alsatian and injected considerable energy into his readings of a wide swath of the traditional repertoire. Although recorded and eventually reissued in "Living Stereo," initially his 1955 taping was published only in monaural format on vinyl. As had the Dorati record, the Munch album added an artistic element, here with its booklet containing five rather straightforward sketches by a very young Andy Warhol.    Munch and his Boston forces rerecorded Daphnis in 1961, but the effort hardly seemed worthwhile, as the two versions are barely distinguishable (and in fact all the CD reissues so far are of the earlier one, as if to suggest that the successor was superflouous). In both performances Munch has his chorus vary their sounds - rather than a uniformly bland (and emotionally inappropriate) "aah," they cry out "hi-ya" in the pirate abduction and intone a soothing "loy loy" in the a capella interlude. But both studio efforts are thoroughly eclipsed by a staggeringly vital July 28, 1961 concert that was issued all too briefly on a 1988 Music and Arts CD (before it was forced off the market under the apparent fear - highly justified - that it would overshadow the authorized studio products) in which orchestra and chorus, despite a few unavoidable slips, play their proverbial hearts out. The intensity is not derived from interpretive exaggerations or bizarre eccentricities. Rather, everything fits together just as it should, but with a heightened attention to expression and added jolts of vigor that have an overwhelming cumulative impact. Just consider the sunrise that opens Part III - it's not just a glorious wash of sound, but Technicolor, 3-D and I-Max. The fidelity is spectacular and the final minutes are emotionally draining. While we all fantasize over how we would improve a performance if only we were in charge, in this instance I simply cannot imagine a more effective rendition. And I'll give critics who still drench the Munch studio recording in superlatives the benefit of the doubt that they've simply never heard this live one. It's one of those astounding, soul-shaking experiences after which no other recording ever sounds quite the same. Beg, borrow or steal a copy (but not mine, please). Munch and his Boston forces rerecorded Daphnis in 1961, but the effort hardly seemed worthwhile, as the two versions are barely distinguishable (and in fact all the CD reissues so far are of the earlier one, as if to suggest that the successor was superflouous). In both performances Munch has his chorus vary their sounds - rather than a uniformly bland (and emotionally inappropriate) "aah," they cry out "hi-ya" in the pirate abduction and intone a soothing "loy loy" in the a capella interlude. But both studio efforts are thoroughly eclipsed by a staggeringly vital July 28, 1961 concert that was issued all too briefly on a 1988 Music and Arts CD (before it was forced off the market under the apparent fear - highly justified - that it would overshadow the authorized studio products) in which orchestra and chorus, despite a few unavoidable slips, play their proverbial hearts out. The intensity is not derived from interpretive exaggerations or bizarre eccentricities. Rather, everything fits together just as it should, but with a heightened attention to expression and added jolts of vigor that have an overwhelming cumulative impact. Just consider the sunrise that opens Part III - it's not just a glorious wash of sound, but Technicolor, 3-D and I-Max. The fidelity is spectacular and the final minutes are emotionally draining. While we all fantasize over how we would improve a performance if only we were in charge, in this instance I simply cannot imagine a more effective rendition. And I'll give critics who still drench the Munch studio recording in superlatives the benefit of the doubt that they've simply never heard this live one. It's one of those astounding, soul-shaking experiences after which no other recording ever sounds quite the same. Beg, borrow or steal a copy (but not mine, please).

- Pierre Monteux, London Symphony Orchestra, Chorus of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden (1959, Decca/London LP and CD; 52:00)

After a brief hiatus, 1959 brought two recordings of immense historical significance. Monteux had prepared and conducted the world premiere of Daphnis 47 years earlier. Here, at age 84, near the very end of his career, he finally documented his interpretation. Like Ansermet, Monteux was one of those extremely rare artists whose interpretive outlook barely changed over a long creative lifetime.   Toscanini, Walter, Klemperer, Bernstein, Celibidache and many others evolved so radically that their earlier work is of an entirely different nature than their final maturity. But we can surmise from the continuity of his multiple recordings of other works that Monteux's 1959 Daphnis probably is a fair representation of how he led the premiere, under the close guidance of the composer, and thus may be as near as we can ever get to Ravel's own approach. The overall impression is one of moderation. While often praised to the heights as the finest of all Daphnis recordings, I must respectfully disagree - everything is in its proper place, the score is followed faithfully, the musicianship is impeccable and the recording is well-balanced, yet something intangible and essential seems missing - the human feeling that others mine and convey. Perhaps this is how Ravel wanted his work performed, and perhaps this is an ideal presentation to accompany the ballet for which it was intended, but as a purely auditory experience it seems too well-groomed. Toscanini, Walter, Klemperer, Bernstein, Celibidache and many others evolved so radically that their earlier work is of an entirely different nature than their final maturity. But we can surmise from the continuity of his multiple recordings of other works that Monteux's 1959 Daphnis probably is a fair representation of how he led the premiere, under the close guidance of the composer, and thus may be as near as we can ever get to Ravel's own approach. The overall impression is one of moderation. While often praised to the heights as the finest of all Daphnis recordings, I must respectfully disagree - everything is in its proper place, the score is followed faithfully, the musicianship is impeccable and the recording is well-balanced, yet something intangible and essential seems missing - the human feeling that others mine and convey. Perhaps this is how Ravel wanted his work performed, and perhaps this is an ideal presentation to accompany the ballet for which it was intended, but as a purely auditory experience it seems too well-groomed.

- Manuel Rosenthal, Orchestre du Théâtre National de l'Opéra de Paris, Choeurs de la Radiodiffusion Télévision Française (1959, Vega LP, Ades CD; 61:00)

Rosenthal's bond with Ravel was the most intimate of all - in 1926 he became the last of Ravel's very few students and remained one of his closest associates. Ravel even arranged for his conducting debut (of Rosenthal's own works). While we have no way of knowing if his esthetic ideals had departed from those of his teacher by the time of this recording, his Daphnis is stunning for its unparalleled depth of atmosphere, which suggests throughout a constant dream-state. It's truly remarkable how much difference a relatively slight slackening of the tempo can make in the quiet portions. In the opening, nocturne and daybreak sections time seems suspended, and Chloé's dance of supplication gains heart-rending poignancy. Yet the overall timing is somewhat deceptive, as Rosenthal's energized sections are substantially faster than the norm, and as the result of the contrast seem to have even further urgency. Thus Chloé's dance seems all the more moving after a frenetic pirate's dance, and the finale seems wilder simply for having followed an exquisitely tender pantomime. Dynamics, too, are extreme, beginning in bare audibility and mounting to shattering climaxes. Along with Munch's unbridled energy, Rosenthal's atmospheric essay is a remarkable and striking presentation. His direct relationship to Ravel, and Monteux's to Daphnis, leave us with the intriguing question of which, if either, of their diametrically-opposed approaches is the more authentic, or whether the composer's own stylistic ideals lay somewhere in between.

- Leonard Bernstein, New York Philharmonic, Chorus of the Schola Cantorum (1961, Columbia LP, Sony CD; 51:25)

Next came the first all-American complete Daphnis - not only an American orchestra but a native-born conductor as well. At the risk of reading too much into that, the result seems quintessentially American - swift, bold, bright, vivid, brash and rather neutral in the sense of being stripped of foreign influence, without any pretense of emulating other cultural approaches. Bernstein presses forward with constant onrushing activity and no pause for sentimentality.   While he later would record with the Orchestra National de France in 1975 (including a sensuous, atmospheric Ravel collection - but no Daphnis), his work here has a fresh-scrubbed quality and is propelled by his characteristic rhythmic flair. At the further risk of stereotyping, his approach is characteristically youthful, not in the sense of reckless audacity but rather in its attention to execution and a fair degree of impatience. Indeed, one of the undeniable virtues of this reading emerges by comparing Bernstein's age at the time (41 - very young for a world-class conductor) with those of all but Dorati who preceded him with full recordings (Ansermet: 69; Inghelbrecht: 73; Munch: 64; Monteux: 84; Rosenthal: 55). Perhaps this is how Monteux would have led it at the premiere. For a relatively neutral, speedy performance it's a fine introduction, but it's also somewhat superficial, as other versions have more to say. Like Dorati's, it's clearly a concert-hall rendition, too fleet to accompany stage action, but with a far greater sense of engagement. While he later would record with the Orchestra National de France in 1975 (including a sensuous, atmospheric Ravel collection - but no Daphnis), his work here has a fresh-scrubbed quality and is propelled by his characteristic rhythmic flair. At the further risk of stereotyping, his approach is characteristically youthful, not in the sense of reckless audacity but rather in its attention to execution and a fair degree of impatience. Indeed, one of the undeniable virtues of this reading emerges by comparing Bernstein's age at the time (41 - very young for a world-class conductor) with those of all but Dorati who preceded him with full recordings (Ansermet: 69; Inghelbrecht: 73; Munch: 64; Monteux: 84; Rosenthal: 55). Perhaps this is how Monteux would have led it at the premiere. For a relatively neutral, speedy performance it's a fine introduction, but it's also somewhat superficial, as other versions have more to say. Like Dorati's, it's clearly a concert-hall rendition, too fleet to accompany stage action, but with a far greater sense of engagement.

- Jean Martinon, Orchestre de Paris, Choeurs du Théâtre National de l'Opéra (1974, EMI LP and CD; 57:00)

It seems fitting to include this last recording by a conductor who had been associated with the composer - Martinon had played violin under Ravel's direction, and thus at least was well aware of Ravel's own style, even if he didn't absorb and adopt it. Indeed, he described Ravel's conducting as being "in contrast to the rather sensual character of his music. Ravel demonstrated a neo-classic temperament in his conducting. His interpretations were curiously rigorous." An acclaimed composer in his own right, Martinon's style was far more expressionistic than impressionistic, and more spiky than sensual. Yet the Debussy and Ravel recordings he cut in his final years reflect neither of these stylistic influences and sound French to the core - relaxed, laid-back and rather conventional, with few distinguishing characteristics, at first somewhat disappointing in its lack of flair and definition (especially in a bland and listless pirates' dance), but perhaps compensating with integrity appropriate to its role as accompaniment to a ballet. The recording, too, is thoroughly blended and somewhat indistinct - perhaps evoking the ambience of a theatre filled with a sound-absorbing audience rather than the controlled sonics of a studio. A decade earlier Martinon had cut the Suite # 2 with the Chicago Symphony (RCA LP, BMG CD). The timings are virtually identical but the earlier suite emerges as more powerful and detailed. Perhaps they serve to exemplify the difference between American and French ensembles and the approaches of their recording teams.

- Pierre Boulez, (1) New York Philharmonic, Camarata Singers (1974; Columbia LP, Sony CD; 54:35); (2) Berlin Philharmonic, Rundfunkchor Berlin (1994; DG CD; 56:50)

Boulez, too, was a French composer/conductor. Indeed, he is the most acclaimed and influential "serious" composer of our time, venturing way beyond exploring extensions of conventional tonality into serial, aleatory and electronic idioms. Yet the vast bulk of his concert programs and recordings are of less venturesome fare, perhaps dictated as a matter of practicality more by audience than personal taste.   While his Berlioz, Mahler and Bruckner often seem cold and calculated (presumably out of a fellow-composer's extreme respect for the sufficiency of the scores), his Debussy and Ravel run the full gamut of emotion, with extreme tempos both urgent and patient. More than any other distinctive feature, Boulez brings out the full splendor of Ravel's variegated orchestration, with constant focus on the ever-shifting and evolving instrumental textures, while maintaining a clear, "modern" sound - analytical without being clinical. His two Daphnis recordings, each part of Debussy and Ravel cycles, are quite similar in approach, although I would give the edge to the Berlin version for its marginally deeper sense of repose, superior execution and sonics that suggest a more natural balance and ambience. A CD bonus is a remarkable performance of Ravel's La Valse which achieves a tense and unsettling balance between Viennese grace and post-war cynicism. While his Berlioz, Mahler and Bruckner often seem cold and calculated (presumably out of a fellow-composer's extreme respect for the sufficiency of the scores), his Debussy and Ravel run the full gamut of emotion, with extreme tempos both urgent and patient. More than any other distinctive feature, Boulez brings out the full splendor of Ravel's variegated orchestration, with constant focus on the ever-shifting and evolving instrumental textures, while maintaining a clear, "modern" sound - analytical without being clinical. His two Daphnis recordings, each part of Debussy and Ravel cycles, are quite similar in approach, although I would give the edge to the Berlin version for its marginally deeper sense of repose, superior execution and sonics that suggest a more natural balance and ambience. A CD bonus is a remarkable performance of Ravel's La Valse which achieves a tense and unsettling balance between Viennese grace and post-war cynicism.

- Charles Dutoit, Montreal Symphony Orchestra and Chorus (1980, Decca LP and CD; 55:55)

During his quarter-century as the head of the Montreal Symphony, Dutoit achieved a miracle akin to Paray in Detroit - creating one of the great French orchestras out of a provincial ensemble in an unlikely New World locale. Recorded toward the outset of his tenure, his Daphnis evokes Monteux's but without the historical resonance. Reflecting Ravel's symphonic approach, the entire score flows smoothly together into a beautifully integrated whole. As with Monteux, there's nothing distinctive or challenging here - just an opportunity to enjoy the sheer sound of this gorgeous score. And when all is said and done, what could possibly be wrong with that?

As usual, I'll take both the credit and the blame for the musical judgments, while acknowledging for the factual information and quotations - and recommending for further reading - the following sources:

As usual, I'll take both the credit and the blame for the musical judgments, while acknowledging for the factual information and quotations - and recommending for further reading - the following sources:

Daphnis & Chloe by Victor Borisov-Musatov (1901)

|

- Davies, Lawrence: Ravel - Orchestral Music (BBC Music Guides, 1970)

- Downes, Edward - notes to the Bernstein/NY Philharmonic LP MS-6260 (Columbia, 1961)

- Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians (1954 edition)

- Ivry, Benjamin: Maurice Ravel - A Life (Welcome Rain Publishers, 2000)

- Kramer, Lawrence: Classical Music and Postmodern Knowledge (University of California Press, 1995)

- Larner, Gerald: Maurice Ravel (Phaidon Press, 1996)

- Lee, Douglas: Masterworks of Twentieth Century Music (Routledge, 2002)

- Longus: Daphnis & Chloe (tr. and introduction by Paul Turner (Penguin, 1956)

- Malloch, William - notes to Maurice Ravel: Ses Amis et Ses Interprètes, CD-703 (Music and Arts, 1992)

- Mawer, Deborah (ed): Cambridge Companion to Ravel (Cambridge University Press, 2000)

- Mellers, Wilfred Man and His Music, volume 4 (Schocken, 1962)

- Nichols, Roger: Ravel Remembered (Norton, 1988) [contains Fokine's Memoirs of a Ballet Master]

- Orenstein, Arbie: Ravel - Man and Musician (Columbia University Press, 1975)

- Orenstein, Arbie (ed): A Ravel Reader (Columbia University Press, 1990) [contains Ravel's 1928 Autobiographical Sketch]

- Ravel, Maurice and Michel Fokine: Daphnis et Chloe [orchestral score] (Durand, 1913)

- Schonberg, Harold: Lives of the Great Composers (3d edition) (Norton, 1997)

- Schult, Richard - notes to the Munch/Boston Symphony CD-278 (Music and Arts, 1988)

- Seroff, Victor: Maurice Ravel (Books for Libraries Press, 1953)

- Zakariasen, Bill - notes to the Boulez/NY Philharmonic LP M-33523 (Columbia, 1975)

Copyright 2013 by Peter Gutmann

|